Statistical Process Control (SPC) charts help teams determine whether a process is stable, predictable, and performing within expected limits. Instead of reacting to defects after they appear, SPC allows organizations to identify unusual patterns early and prevent quality failures or operational drift.

In 2026, industries that rely on continuous measurement such as manufacturing, logistics, healthcare, food production, and service operations use SPC as a core monitoring tool.

This guide explains how SPC charts are constructed, how control limits work, and when these charts provide reliable support for process decisions.

What Statistical Process Control (SPC) Charts Actually Show

SPC charts are designed to separate normal process variation from signals that indicate a meaningful change in performance. They help teams determine whether a process is stable, capable of meeting requirements, or beginning to drift.

By plotting data in time order, SPC charts highlight patterns such as shifts, trends, cycles, or sudden spikes that require investigation. These insights support quality control, root cause analysis, and operational decision making across both high-volume industries and service environments.

Core Components of a Statistical Process Control SPC Chart

An SPC chart is built on a structured set of elements that help teams interpret process behaviour accurately. Each component plays a specific role in distinguishing routine variation from true process changes. Understanding these parts is essential before choosing chart types or interpreting patterns.

1. Data Points and Time Order

Every SPC chart is constructed using measurements collected at regular intervals. The chronological sequence is critical because it shows how the process behaves over time rather than in isolated data sets.

2. Central Line

The central line represents the process’s average or median performance. It provides the baseline against which all future points are compared.

3. Upper and Lower Control Limits (UCL and LCL)

These limits are calculated from actual process data. They indicate the expected range of natural variation. Points outside these boundaries usually signal a significant change that requires investigation.

4. Standard Deviation Logic

SPC relies on the distribution and spread of data, so standard deviation is used to calculate control limits and determine how tightly or loosely the process is performing.

5. Sampling Frequency and Subgrouping

Sampling needs to follow a consistent pattern. Subgrouping helps smooth noise and highlights meaningful variation, especially in fast-moving processes.

6. Rules for Interpreting Variation

SPC charts identify signals such as runs, trends, spikes, or clusters. These rules help teams detect abnormalities that do not immediately cross control limits but still suggest emerging issues.

Types of Statistical Process Control (SPC) Charts with Use Cases

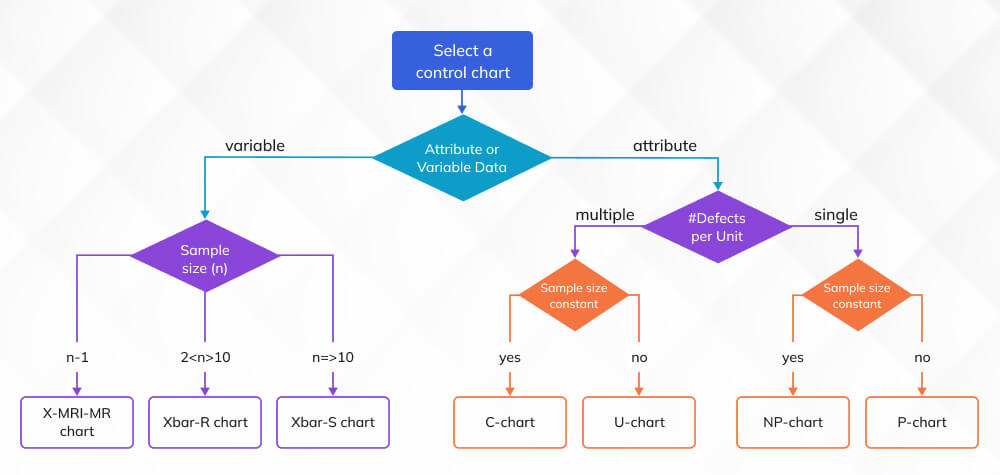

SPC charts are selected based on the type of data being measured. Choosing the correct chart ensures that variation is interpreted correctly and that control limits reflect the true behavior of the process.

Below are the main chart categories used in modern operations, along with when each one applies.

|

SPC Chart Types and When to Use Them |

||

| Category | Chart Type | When to Use |

| Variable Data Charts | x̄–R Chart | When data is collected in small subgroups. Suitable for monitoring measurements like weight, time, or thickness where within-group variation matters. |

| x̄–S Chart | When subgroup sizes are larger or variation needs precise tracking. Common in high-volume or complex processes. | |

| Individuals and Moving Range (I-MR) Chart | When only one measurement is available at each sampling point. Used in healthcare, chemical processes, and labs. | |

| Attribute Data Charts | p-Chart | When tracking the proportion of defective units in varying sample sizes. Useful for quality inspections with pass or fail outcomes. |

| np-Chart | When sample size is constant and the goal is to count the number of defectives. Works well for repetitive inspections. | |

| c-Chart | When counting the number of defects in a constant inspection area or time period. Suitable for error or incident monitoring. | |

| u-Chart | When inspection volume varies and defects must be evaluated per unit. Used in production runs, batches, or service transactions. | |

How to Create an Statistical Process Control (SPC) Chart? (Step-by-Step Workflow)

Creating an SPC chart requires more than inserting data into a template. The goal is to build a chart that reflects the real performance of a process and produces signals that teams can trust. This workflow mirrors how SPC is implemented in regulated manufacturing, food processing, healthcare laboratories, and other high-reliability operations.

1. Define the Measurement Strategy

Start by specifying the characteristic being monitored, the measurement units, the device used, and the sampling frequency. The sampling plan must match the natural cycle of the process. If the process produces units continuously, data should be collected at consistent intervals. If the process produces batches, sampling should be aligned with batch completion. Clarify whether data will be collected individually or in subgroups, because chart selection depends on this structure.

2. Validate Data Quality

Before any calculations, confirm that the dataset is complete, recorded at uniform intervals, and free of transcription errors. Check for drift in measurement devices by reviewing calibration records. Identify outliers that came from measurement mistakes rather than true process shifts. SPC charts cannot correct flawed data. If the input is unreliable, the resulting limits and signals will be misleading.

3. Calculate the Central Line and Variation

For variable charts, compute the mean and the range or standard deviation for each subgroup. For attribute charts, calculate the proportion, count, or rate of defects. These values characterise the natural performance of the process. The central line must represent actual behavior, not a target or specification.

4. Set Statistically Valid Control Limits

Use established formulas to calculate the upper and lower control limits. These limits must come from process data, not from specification tolerances. Control limits represent what the process normally does. Specifications represent what the customer requires. Confusing the two leads to incorrect conclusions and unnecessary adjustments.

5. Plot Data in Time Order

Arrange all points chronologically. SPC charts become meaningful only when variation is viewed across time. Time order exposes trends, cycles, recurring issues, and sudden changes that remain invisible in simple summary statistics.

6. Apply Interpretation Rules

Use well-established rules such as Western Electric or Nelson to detect subtle changes. These rules help identify conditions like sustained drifts, clusters of points near limits, alternating patterns, and unusual cycles. Many of these signals occur long before the process produces defects, which is why SPC is a preventive tool rather than a reactive one.

7. Document Findings and Actions

After interpreting the chart, document observations and corrective actions. This includes identifying possible special causes, testing hypotheses with operators or engineers, and confirming whether each change stabilised the process. SPC only improves performance when the insights translate into controlled adjustments on the production floor.

When Should Statistical Process Control (SPC) Charts Be Used?

SPC charts are not general-purpose graphs. They are analytical tools that reveal how a process behaves over time. They are most effective when the process has a consistent rhythm, measurable outputs, and enough data to separate expected variation from true changes. The conditions below describe when SPC charts provide reliable, actionable insight rather than noise.

1. When the Process Is Repetitive

SPC is most effective in environments where the same type of output is produced again and again. Examples include filling operations, packaging lines, machining steps, clinical test runs, call center handling times, and laboratory measurements. The consistency of these processes allows SPC to track natural variation and detect meaningful shifts before they grow into defects or service failures.

2. When Early Detection Is Needed

Many processes deteriorate gradually rather than suddenly. Equipment wears down, operators adopt different techniques, environmental conditions shift, or raw materials change over time. SPC identifies subtle drift through patterns such as trends, cycles, and runs. These signals appear long before the process crosses defined limits, which gives teams time to investigate and correct issues before they affect customers.

3. When Stability Must Be Proven First

SPC is a prerequisite for meaningful capability studies. A process must show stable behaviour before metrics such as Cp or Cpk can be trusted. If a process is unstable, capability indices will misrepresent its actual performance and lead to decisions based on misleading data. SPC provides the stability check needed before capability evaluations or specification reviews.

4. When Compliance Requires Monitoring

Industries such as pharmaceuticals, medical devices, automotive, aviation, and food manufacturing often require documented evidence of process control. SPC charts provide visual proof of consistent performance and support audit trails. Regulators expect teams to detect and investigate special-cause variation, not simply test end products.

5. When Improvement Results Need Verification

Lean and Six Sigma projects rely on SPC charts to confirm whether process changes achieved the expected improvement. SPC shows whether the new process holds steady over time and whether any gains eventually erode. This verification step prevents premature conclusions and supports sustained improvements.

6. When High-Volume Data Needs Structure

High-volume environments produce large amounts of data. SPC charts condense that data into a clear signal that operators and engineers can act on. They help prevent overreaction to normal variation while ensuring that true problems are not overlooked.

When Statistical Process Control (SPC) Charts Should Not Be Used

SPC charts provide meaningful insight only when the process and data structure support statistical control. The following situations are unsuitable for SPC because the charts cannot produce reliable signals.

1. When the Process Lacks Consistency

SPC requires a stable, repeatable sequence of operations. One-off tasks, irregular service work, or processes with constantly changing steps do not generate the continuity needed for valid control limits.

2. When Measurements Are Subjective

Processes that rely on opinions, visual judgments, or interpretive scoring do not produce data that reflect true process behaviour. SPC cannot separate natural variation from human bias in subjective metrics.

3. When Data Is Insufficient or Irregular

Control limits depend on sufficient and consistent data. Very small datasets or irregular sampling intervals produce unstable charts that resemble noise rather than true process performance.

4. When the Process Keeps Changing

If equipment settings, workflows, recipes, or inspection criteria change frequently, the chart mixes multiple process states. SPC must be applied only after the process is standardised and stable.

Conclusion

SPC charts give teams a structured way to understand how a process behaves and whether performance is shifting in ways that require action. When used correctly, they expose early variation patterns, strengthen quality control, and support long-term process stability. Modern operations rely on SPC as part of everyday monitoring because it helps prevent defects rather than reacting to them.

Professionals who want to apply SPC with confidence benefit from formal training in quality methodologies. Invensis Learning offers programs such as Lean Six Sigma Green Belt, Lean Six Sigma Black Belt, and Quality Management certifications. These courses build the analytical and statistical skills needed to interpret variation accurately and make informed decisions based on SPC data.