Modern product teams work with several early-stage release models, including MVP, MMP, and MLP, each designed to support a different stage of learning, validation, and market readiness.

These models help teams build intentionally, release with purpose, and move from idea to value with measured investment. When selected and sequenced correctly, they reduce risk, protect resources, and create a clear path from initial hypotheses to sustainable adoption.

This guide explains how each model contributes to product maturity, how they relate to one another, and how teams can apply them to structure releases with clarity, confidence, and focused outcomes.

The Product Validity Spectrum Explained

Early-stage product models such as MVP, MMP, and MLP are not independent concepts. They sit on a spectrum that moves from rapid validation to market readiness and eventually to long-term retention. Each point on this spectrum represents a different level of investment, user exposure, and certainty.

An MVP focuses on learning. An MMP focuses on selling. An MLP focuses on user attachment. Additional variants such as MAP or MSP support specific strategic goals, but all of them map back to how much risk the team is willing to take before scaling.

Seeing these models as stages rather than standalone definitions helps product teams avoid overbuilding, misjudging readiness, or advancing too quickly before evidence supports the next step.

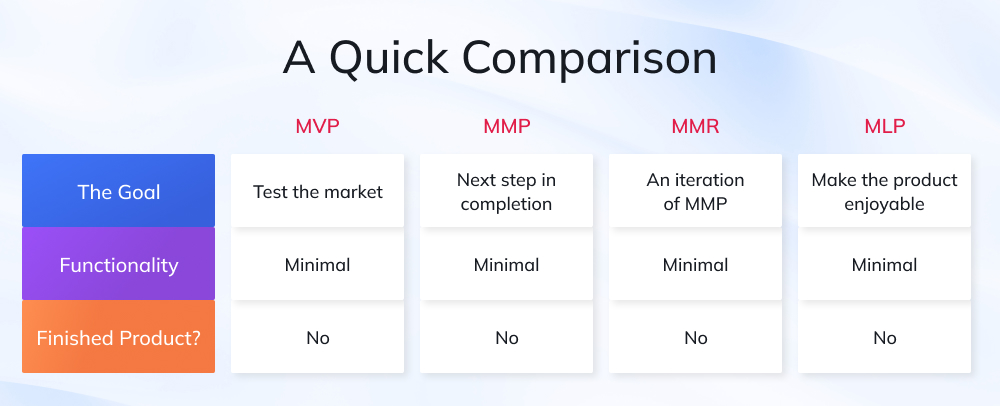

Comparison Table: MVP vs MMP vs MLP vs MAP |

||||

| Criteria | MVP | MMP | MLP | MAP |

| Primary Goal | Validate core assumption through real user behavior | Release a usable and reliable version to paying or active users | Create emotional connection and strong preference | Deliver clear superiority and differentiation |

| Focus Area | Learning and hypothesis testing | Stability, usability, and market readiness | Retention and product experience quality | Competitive advantage and standout value |

| Scope | Single core action that proves value | Full problem resolution for initial users | Smooth experience with meaningful value moments | Enhanced capabilities or experience beyond competitors |

| Quality Expectation | Acceptable, limited, and temporary | Predictable, steady, and supportable | Enjoyable, intuitive, and rewarding | Remarkable, polished, and notably better |

| Success Metric | Evidence that justifies next step | Paid use, repeat usage, and reduced support friction | Emotional response and natural retention | Market separation and strong public advocacy |

| Time to Market | Fastest | Moderate and controlled | After traction proves potential | After validated adoption or product-market fit |

| Risks When Misused | False validation or wasted learning | Early reputation damage | Misplaced focus on aesthetics | Overbuilding before market proves differentiation |

Minimum Viable Product (MVP)

An MVP is the smallest functional version of a product that proves or disproves a core assumption through real user behaviour. It is not a cut-down version of a future product or a partial demo meant only for marketing. The goal is to validate learning as fast as possible, using minimal resources, while still exposing users to the core value the product claims to offer. A good MVP reduces uncertainty and guides teams toward evidence-based decisions instead of assumptions, intuition, or stakeholder preferences.

What Defines a Meaningful MVP

A meaningful MVP must let the user successfully complete one essential action connected directly to the product’s value hypothesis. This action should mirror the real behaviour the team wants to test, whether users find the solution valuable, usable, or worth engaging with. If the workflow cannot be completed end-to-end, the experiment becomes inconclusive, and the data loses reliability.

A realistic MVP is:

-

Usable Enough to Produce Behaviour-Based Insight

The interface or workflow should not block users from interacting with the core function. It doesn’t need polish, animations, or branding, but it must allow users to perform the intended task in a way that accurately reveals their interest, motivations, and friction points. For example, if testing whether users will schedule a service online, the scheduling must actually work, even if the backend is manually operated.

-

Limited Enough to Avoid Long Development Delays

Any feature that does not directly contribute to validating the hypothesis should be excluded. Adding extra functionality introduces noise into the experiment and extends development time. The power of an MVP lies in its focus, not in the completeness of its feature set. A common rule is: If a feature doesn’t change the decision you will make after the test, it should not be in the MVP.

Where MVPs Commonly Fail

Many MVPs fail because teams unintentionally work against the purpose of the model. Some frequent failure patterns include:

Overbuilding to Avoid Negative Feedback

Teams often add unnecessary features or polish because they fear users will reject an unrefined version. Ironically, this delays learning and increases the cost of discovering that the core idea might still be wrong.

Testing Interest Instead of Behaviour

Measuring clicks, sign-ups, or survey responses may show curiosity, but not commitment. Superficial signals create false confidence. An MVP must reveal actual usage, not theoretical desire.

Producing Vanity Metrics Instead of Validation

If the data collected cannot clearly answer a decision-making question, for example, “Should we continue building this?”, then the MVP is ineffective. Vanity metrics include page visits, likes, or impressions that do not reflect real adoption or value.

Missing the Core Hypothesis Completely

Sometimes the MVP tests secondary features or cosmetic ideas because they’re easier to build. This leads to misleading insights and decisions based on noise rather than meaningful behaviour.

Practical Formats that Qualify

There is no single correct shape for an MVP. The best format is the one that delivers the fastest and clearest validation with the least engineering effort. Common and effective MVP formats include:

A Working but Limited Workflow Screen

A basic interface that performs one essential task, for example, uploading a file, generating a quote, or completing a simple workflow.

A Manual or Concierge MVP

Behind a simple front-end interface, the team manually completes the task that software will eventually automate. This is ideal when validating complex logic without building the full system.

A Click-Through Prototype Testing Completion Intent

Interactive prototypes (Figma, InVision) that simulate experience and measure whether users attempt to complete a workflow. These are useful when behaviour, path selection, or drop-offs matter more than backend accuracy.

A Single-Feature Live Release

Launching only the most critical feature in a real environment to observe adoption, retention, or performance under real-world conditions.

Regardless of the format, the goal of an MVP is validated learning, not revenue, retention, or scale. Once the team knows what works, and what doesn’t, the product can progress confidently toward the MMP stage.

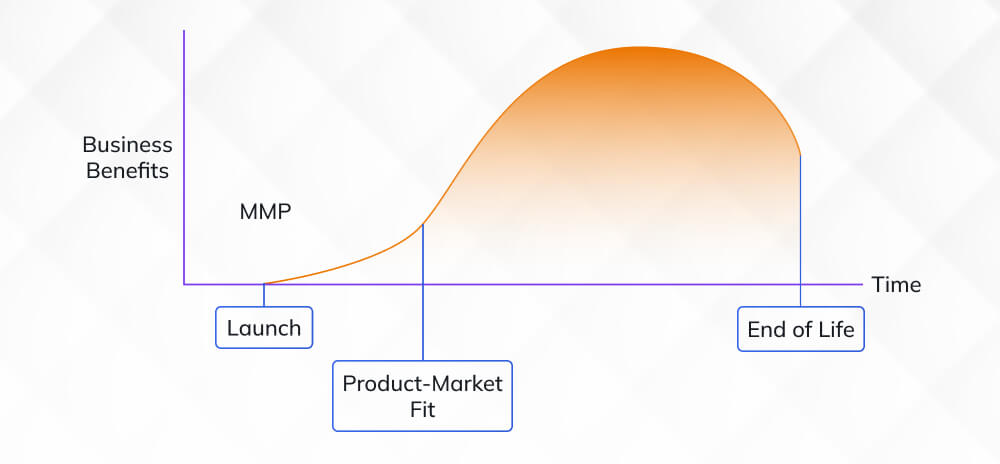

Minimum Marketable Product (MMP)

An MMP is the first version of the product that is solid enough for real customers to use, rely on, and pay for. It moves beyond the experimental nature of an MVP and focuses on delivering consistent value with a baseline of quality that supports real-world usage.

While it may still represent an early stage of the product’s evolution, an MMP must withstand everyday user needs, meaning it should be dependable, stable, and intuitive enough that users can complete their tasks without hand-holding or workarounds.

Unlike a full-featured product, the MMP includes only the essential set of capabilities required to deliver meaningful outcomes. However, those capabilities must perform reliably. The MMP sets the foundation for onboarding real customers, generating early revenue, and proving that the solution can support repeated usage, not just initial interest.

How an MMP differs from an MVP

The key difference lies in purpose and readiness:

- MVP ? Built to learn

An MVP validates assumptions about value, demand, or behaviour. Its main job is to generate insights. - MMP ? Built to serve

An MMP is the first version that is meant for active users, not test participants. It needs to function with a level of quality that protects customer trust and the brand’s reputation.

An MMP must also support the operational requirements of being a real product:

- Onboarding flows

- Help documentation

- Customer support pathways

- Pricing or subscription structure

- Predictable performance

This level of maturity signals that the product is ready to operate in the market and deliver consistent value in exchange for revenue.

What an MMP must achieve

This stage represents the transition from “testing” to “delivering.” The product must now serve real users with real expectations, which means the standards are much higher than in an MVP.

Each requirement here ensures that the product can support everyday usage without causing friction or doubt.

Solve a Complete User Problem

The product must address the primary problem end-to-end, not partially. Users should be able to achieve a full outcome without feeling that key steps are missing or still experimental. If they cannot rely on it for real work, it is not yet an MMP.

Provide Predictable Experience and Outcome Quality

Consistency is essential. The workflow should behave consistently every time, and the user should trust that the system will work when needed. Predictability reduces frustration and forms the basis for repeat usage, a key indicator for early revenue.

Meet the Minimum Reliability Level for Public Use

This includes acceptable performance speed, uptime, error handling, and stability. A marketable product cannot crash often or force users to retry core tasks. Even if the interface is simple, it must perform reliably in real-world conditions where users have different devices, environments, and expectations.

Risks if Executed Incorrectly

Because MMP sits at the intersection of value delivery and early revenue, mistakes at this stage can create long-term damage. These risks highlight what happens when teams ship too soon or build too much.

Understanding these risks helps teams protect both customer trust and internal momentum.

Releasing an MMP That Behaves Like an MVP

If the product still feels unstable, incomplete, or “beta-like,” early users may form negative impressions that are hard to reverse. This results in:

- Customer churn

- Poor early reviews

- Increased support load

- Damaged reputation

A shaky MMP creates long-term credibility issues even if the idea is strong.

Adding Too Many Features Too Soon

Overbuilding an MMP slows down time-to-market and increases the cost of proving value. Teams often add features they think users will want instead of focusing on what users actually need to succeed. These additions rarely increase adoption but significantly delay revenue.

Losing Focus on Market Credibility

The purpose of an MMP is not to deliver a “complete” product; it is to deliver a trustworthy, dependable, value-creating experience that generates confidence in the solution.

A well-crafted MMP establishes early-market credibility and sets the foundation for scaling toward MLP and beyond.

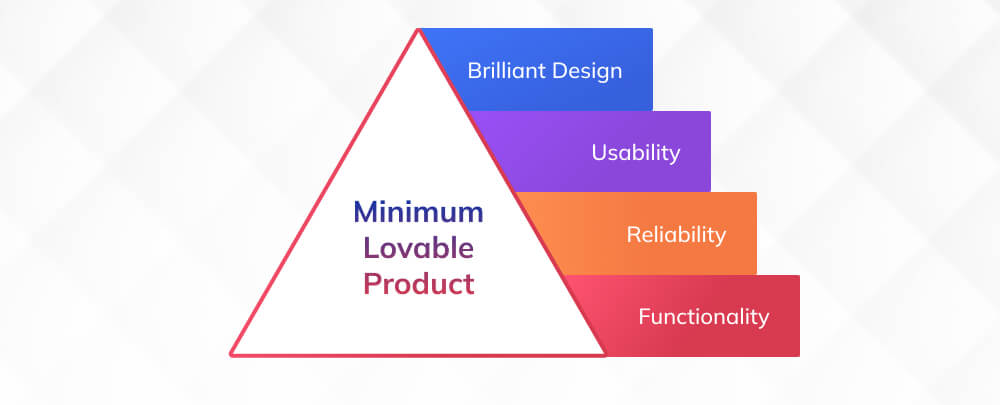

Minimum Lovable Product (MLP)

An MLP is the version of a product that not only solves a problem but also creates a positive emotional response, leading to stronger retention, repeat usage, and user advocacy. While an MVP validates viability and an MMP delivers reliability, the MLP introduces the early layers of delight, connection, and experiential value.

The goal is not to polish every corner of the product or add unnecessary flair. Instead, the focus is on elevating the experience to a point where users feel the value, a connection that transforms the product from “usable” to “preferable.”

When an MLP Becomes Relevant

Before moving toward an MLP, the team must confirm that the product works well enough to support real adoption. This stage is not about experimentation; it’s about amplifying what users already appreciate.

The shift happens when teams need to strengthen long-term engagement, reduce churn, and differentiate themselves in a crowded market.

Teams transition to an MLP once the product has demonstrated:

- Functional stability

- Early traction or revenue

- Evidence of adoption potential

At this point, the strategic focus moves from validation to retention and differentiation. In markets where alternatives are easy to switch to, creating emotional attachment becomes a competitive advantage. MLP is especially relevant in sectors like SaaS, consumer apps, education platforms, wellness apps, and lifestyle-based tools where the experience matters as much as the functionality.

What Gives an MLP its Impact

An MLP stands out because it elevates moments that matter. Rather than improving every detail, it identifies the key interactions that carry emotional weight and enhances them intentionally.

These enhancements strengthen connection, reduce friction, and create experiences users want to return to.

A Smooth and Friction-Free Core Experience

Fewer steps, clearer navigation, quick responses, and seamless task completion all build trust. When users feel that the product “just works,” their emotional energy shifts from frustration to appreciation.

Clear Value Moments That Feel Rewarding or Empowering

Value moments are the points where users feel a sense of progress, success, or relief. This could be completing a task faster, receiving smart recommendations, or unlocking a meaningful insight. These moments strengthen the perceived value of the product.

Thoughtful Touches That Encourage Continued Use

These are not random “delight features,” but intentional design elements, supportive microcopy, intuitive animations, personalized suggestions, or subtle UX cues. When executed well, these touches feel natural, supportive, and distinctly memorable.

Common Mistakes

MLP is often misunderstood because teams assume “lovability” means adding style, colour, or visual polish. In reality, emotional connection comes from how well the product supports the user’s needs, not how fancy it looks.

Understanding the difference between cosmetic enhancements and meaningful experience improvements is essential to avoid wasted effort.

Over-Focusing on Visual Design Instead of Experience Quality

A polished UI without functional improvements creates a shallow upgrade. Users might admire the look but still feel frustrated if core workflows remain confusing or slow.

Adding Delight Features That Don’t Support the Core Journey

Animations, badges, or novelty features can distract users instead of empowering them. Lovability emerges from reduced friction and meaningful outcomes, not from decorative additions.

Confusing MLP With the Final Product Vision

The MLP is not the finished product. It is a strategically enhanced version designed to strengthen connection and encourage continued usage while still allowing space for future growth and refinement.

MAP and Related Early-Stage Product Models

Several additional product maturity terms appear in modern product conversations, often without clear context. These models are useful only when applied intentionally, not as buzzwords or renamed MVPs. Each carries a different decision purpose, not just a different label.

MAP (Minimum Awesome Product)

MAP represents a product stage where the experience is not only reliable but also distinctive enough to outperform competing solutions. It builds upon an MLP by introducing strong differentiation in workflow, speed, convenience, or outcome. MAP is relevant in markets where competitors already have functioning and lovable solutions, and standing out requires clear superiority, not just satisfaction.

MSP (Minimum Sellable Product)

An MSP focuses on commercial readiness, not emotional or experiential quality. It is often relevant in B2B, enterprise, or regulated markets where contractual requirements, compliance, or documentation matter more than delight. MSP prioritises sale requirements, not retention drivers.

MLDP (Minimum Learnable and Deployable Product)

MLDP applies in environments where training, onboarding, and operational adoption are critical factors, such as healthcare, SaaS workflow platforms, or industrial software. Here, the focus is on whether users can quickly understand and adopt the product with minimal support friction.

Why Do these Models Cause Confusion

Teams sometimes rename an MVP or MMP to sound innovative, which weakens alignment and decision clarity. These models only add value when they represent different success criteria, not different vocabulary.

How These Models Fit Into a Product Roadmap

MVP, MMP, MLP, and related variants are not interchangeable. They represent different maturity thresholds that guide how much to build, how long to invest, and which type of user exposure is appropriate at each point. Treating them as a roadmap helps teams avoid overbuilding early or rushing into scale without proof.

1. MVP for Evidence and Direction

Use the MVP to validate assumptions about problem, value, and user behaviour. The goal is to turn uncertainty into clarity with the smallest realistic experiment.

2. Transition to MMP for Real Use and Early Revenue

Once assumptions hold true, the product shifts into a state where customers can use it reliably and the business can begin forming repeatable value exchange. This is often where onboarding, support, and pricing models become relevant.

3. Progress to MLP for Retention and Differentiation

After the product is proving useful and stable, the focus moves toward creating preference and loyalty, not just functionality. Retention signals become the primary metric.

4. MAP, MSP, or MLDP Based on Market Context

These optional stages apply only when competitive intensity, compliance, enterprise adoption, or onboarding complexity become strategic drivers.

Roadmaps that respect these maturity boundaries minimise waste and maximise validated learning, rather than chasing feature volume or internal opinions.

Choosing the Right Model for Your Product Stage

Selecting between MVP, MMP, MLP, and other variants is not a creative preference. It is a risk-based decision that depends on market conditions, team capability, and the type of evidence needed before investing further.

Assess the level of Uncertainty

If the team does not yet know whether users want the solution or if the problem framing is still unclear, an MVP is appropriate. When the uncertainty shifts from value to execution, the product is ready for MMP.

Match Scope to Market Tolerance

Products for consumer users, competitive categories, or lifestyle-driven usage often require movement toward MLP sooner than enterprise or compliance-driven products, where reliability and scale matter more than emotional response.

Align with Organisational Capacity

A lean team with limited engineering depth should not jump to MLP or MAP before proving value. Larger organisations with tested platforms and shared infrastructure can reach higher maturity levels faster.

Use Data, not Opinions, to Decide Transitions

Signals such as feature completion rate, repeated usage patterns, willingness to pay, referral intent, customer support load, and onboarding friction are more reliable indicators than stakeholder excitement.

A good choice reduces risk, waste, and time to clarity rather than trying to impress users, executives, or investors.

Mistakes Companies Make With MVP, MMP, and MLP

Misunderstanding these models often leads to wasted development cycles, unclear product direction, and premature scaling. The issues below are among the most frequent and costly across startups, SaaS products, and enterprise innovation teams.

- Building an MVP that behaves like an unfinished MMP

Many MVPs fail because they are overbuilt with secondary features, visual polish, and long delivery timelines. This removes the speed advantage and results in delayed learning. - Launching an MMP that still feels like an MVP

If the first market-facing product lacks reliability, users treat it as a weak solution rather than a promising early version. This produces negative perception that is difficult to repair. - Treating MLP as a cosmetic upgrade

Teams sometimes assume that design, branding, or UI enhancements create “lovability.” Emotional value comes from reduced friction, meaningful outcomes, and intuitive experience, not animation or colour. - Progressing through stages without measurement

Advancing from MVP to MMP or MLP without defined success metrics converts product development into guesswork. Stage transitions must be supported by real signals, not stakeholder enthusiasm.

Conclusion

MVP, MMP, and MLP are not alternative names for the same release stage. They represent distinct checkpoints that guide how much to build, what to measure, and when to scale. Teams that treat these models as a maturity sequence gain faster validation, controlled investment, and clearer retention signals, while avoiding the build-heavy habits that lead to slow or unfocused launches.

Professionals who want to strengthen product delivery discipline, validation approaches, and roadmap planning can enroll in relevant programs at Invensis Learning, including Certified Scrum Product Owner, Agile Scrum Master, Project Management Certification, and PRINCE2. These courses help teams manage scope, prioritize evidence, and align releases with measurable outcomes rather than assumption-driven execution.