A Non-Conformance Report (NCR) is one of the most important quality and compliance tools used to document and resolve situations where products, services, processes, or records do not meet approved requirements.

Rather than focusing on fault or blame, an NCR provides a structured way to record what happened, contain impact, trace contributing factors, and drive improvement.

Organisations use NCRs to maintain quality standards, verify compliance, support audits, and build long-term process reliability.

When applied correctly, NCRs strengthen transparency, reduce recurrence, and create measurable operational learning instead of repeated correction cycles.

What a Non-Conformance Report Is and Why It Exists

A Non-Conformance Report (NCR) is a formal record used to document any output, activity, or condition that does not meet an approved requirement. For example, specifications, standards, procedures, regulatory expectations, or contractual commitments. It provides fact-based documentation, ensures controlled handling of deviations, and leads to verified corrective actions that prevent recurrence.

The purpose of an NCR is not to assign blame. It exists to create traceability, protect product or service integrity, support compliance obligations, and ensure that every deviation is evaluated, contained, investigated, and properly closed. When consistently applied, NCRs become a reliable mechanism for improving process capability and strengthening operational discipline across the organisation.

Trigger Points That Require an NCRAn NCR is raised whenever a confirmed or suspected deviation occurs that could affect compliance, performance, safety, customer requirements, or internal standards. It applies to both visible defects and situations where the result may still appear acceptable but was achieved outside approved methods or controls. Typical triggers include:

Raising an NCR at the correct moment preserves accuracy, evidence, and corrective-action quality. |

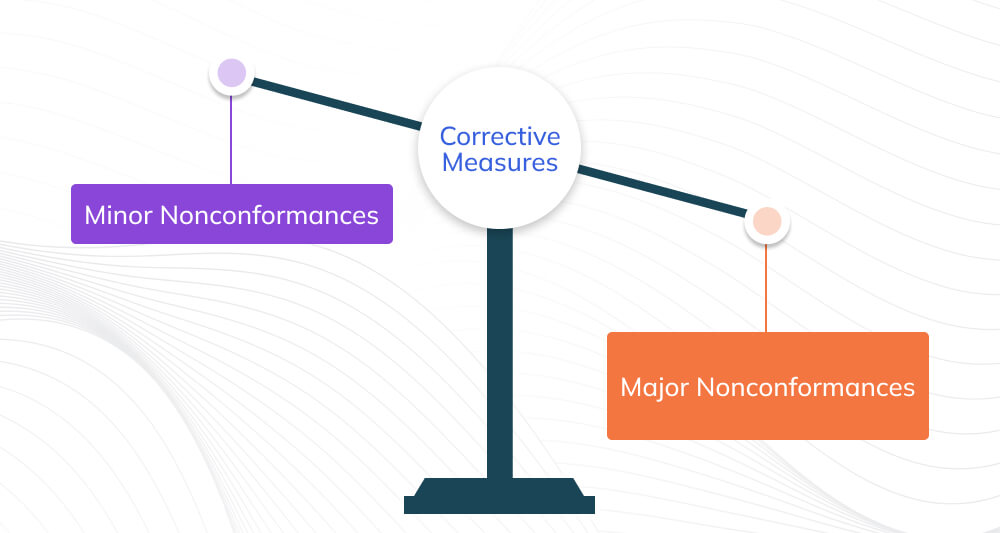

Types of Non-Conformance

Across most quality-driven organisations, non-conformances are generally grouped into two severity levels. This classification determines how the issue is documented, investigated, escalated, and closed. The severity level is based on risk and consequence, not on frequency or visibility.

Minor Non-Conformance

A minor non-conformance is a deviation that does not compromise product performance, user safety, regulatory compliance, or customer expectations. These events still require correction and documentation, but the impact is localised and low-risk, and the resolution typically involves straightforward corrective actions without extensive cross-functional investigation.

Examples of Minor Non-Conformance

- A form with missing supporting details where traceability is still intact.

- A label placement or format that deviates from instruction but does not misidentify the product.

- Using an approved tool or fixture but not recording the usage step in sequence.

- A visual imperfection on a cosmetic, non-functional surface of a component.

- An internal deadline missed without affecting delivery, compliance, or test validity.

A minor non-conformance is still an official record, not an informal “note to fix later.”

Major Non-Conformance

A major non-conformance is a deviation that impacts or could reasonably impact safety, performance, compliance, product integrity, or controlled documentation. These cases require formal investigation, containment, root-cause analysis, and documented corrective and preventive action (CAPA). They may also trigger customer notification, recall assessment, or regulatory reporting depending on the sector.

Examples of Major Non-Conformance

- A product or batch released that does not meet required specifications or legal limits.

- Critical records missing or incomplete in a way that prevents audit verification.

- Processing or testing performed outside approved conditions for a regulated product.

- Mislabeling that could lead to incorrect identification, installation, dosage, or use.

- Environmental, safety, contamination, or hygiene conditions that elevate risk beyond tolerance.

A major non-conformance signals potential systemic failure, not simply an isolated event.

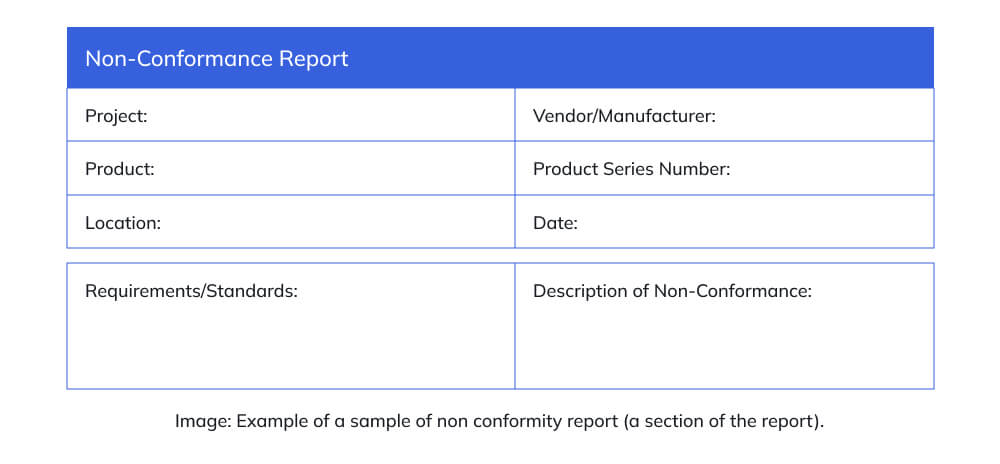

Core Information That a Non-Conformance Report (NCR) Must Capture

An NCR must present a clear, factual, and traceable record of the deviation so that anyone reviewing it later can understand what happened, where it occurred, why it matters, and how it was addressed. The focus is on accurate information, objective evidence, and decision-support clarity, not lengthy narratives or assumptions.

To ensure consistency, a well-written NCR typically includes:

- Identification details such as reference number, date, location, and responsible department.

- Exact description of the deviation written factually, without opinions or assumptions.

- Applicable requirement that was not met (specification, SOP, drawing, standard, contract, or regulation).

- Immediate containment or isolation actions taken to stop further impact or distribution.

- Evidence records such as measurements, photos, lot numbers, inspection results, or attached documents.

- Impact assessment covering safety, compliance, performance, and customer exposure.

- Next actions including escalation, investigation assignment, or temporary disposition approval.

The NCR must support traceability and verification, which means all content should be clear, complete, and reviewable, even by someone who was not involved.

Non-Conformance Report (NCR) Workflow From Detection to Closure

An NCR moves through a structured path to ensure that the deviation is documented, contained, analysed, and closed with verified corrective actions. Each stage must be completed before moving to the next to avoid superficial closure or repeat issues.

1. Detection and Initial Recording

The process begins when a deviation is observed, reported, or identified during inspection, audit, or routine monitoring. The facts are documented immediately so that details are fresh, complete, and traceable.

2. Screening and Classification

The NCR is reviewed to determine whether it is minor or major based on risk, exposure, and potential customer, compliance, or safety impact. This decision determines the level of investigation and approval required.

3. Containment and Temporary Actions

Potentially affected products, batches, documents, or processes are isolated or controlled. The goal is to prevent further use, release, or continuation until the issue is understood.

4. Root Cause and Risk Analysis

The deviation is analysed using structured problem-solving to identify the true contributing factors rather than only the visible symptom. This stage connects the issue to data, process flow, environment, or human-factor drivers.

5. Corrective and Preventive Action Planning

Actions are defined to eliminate the identified cause and to prevent recurrence in similar or related areas. The plan may involve training, tooling adjustments, documentation revision, supplier engagement, or process redesign.

6. Verification and Formal Closure

Closure is granted only when actions are completed, evidence is reviewed, and the effectiveness of the solution is confirmed. The NCR record is then archived for future reference, audits, and trend analysis.

Roles and Accountability Within the Non-Conformance Report (NCR) Process

An NCR is effective only when responsibilities are clearly assigned and followed throughout the process. Each stage requires ownership so that issues do not stall, become incomplete, or close without proper verification.

The process typically begins with the reporter, the individual who identifies the deviation and records it factually. Once logged, the NCR is routed to an assigned owner or evaluator, who confirms scope, classification, and required actions.

Responsibility then shifts to an approver, usually a quality or operations authority, who confirms that the investigation, root cause, and corrective actions are suitable for the level of risk involved.

Final oversight lies with a verifier or auditor, who ensures that actions were implemented correctly, evidence is complete, and effectiveness has been proven before formal closure.

Clear accountability prevents NCRs from becoming administrative tasks and strengthens both learning and long-term process reliability.

Common Mistakes in Non-Conformance Report (NCR) HandlingEven well-designed NCR systems fail when the reporting, investigation, or closure approach becomes routine instead of analytical. The purpose of an NCR is to capture facts, learn from deviations, and prevent recurrence, so mistakes in handling can weaken both compliance and improvement value.

|

Improving Non-Conformance Report (NCR) System Maturity

An NCR process becomes valuable when it evolves from simple documentation into a reliable improvement and decision-support mechanism. Maturity is demonstrated not by the number of NCRs raised or closed, but by how consistently the organisation learns from them and strengthens prevention controls. A mature NCR system prioritises clarity, traceability, accountability, and measured effectiveness.

Improvement typically involves four focus areas:

- Structured and standardised documentation: Clear templates, terminology, and evidence expectations reduce interpretation errors and improve review quality.

- Evidence-ready records and attachments: Supporting proof, not verbal summaries, ensures that audits, reviews, and investigations remain objective.

- Cross-functional visibility and review: Including relevant stakeholders expands insight and prevents silo-based conclusions or local fixes.

- Trend-based improvement focus: Analysing NCR history supports pattern recognition, predictive improvement, and prioritised risk mitigation.

A mature NCR process helps organisations protect quality, compliance, and operational excellence without turning every event into an administrative workload.

Conclusion

A Non-Conformance Report is most effective when treated as a quality improvement tool rather than a compliance obligation. When the record is factual, the investigation is structured, and the actions are verified, NCRs help organisations reduce repeat deviations, protect product integrity, and maintain regulatory and customer confidence. With the right process, an NCR system becomes a data-driven improvement asset instead of isolated documentation.

Professionals who want to strengthen skills in deviation management, corrective action planning, and process improvement may consider relevant training from Invensis Learning, including Lean Six Sigma Yellow Belt, Lean Six Sigma Green Belt, Lean Six Sigma Black Belt, and Root Cause Analysis program. These programs build capability in structured problem solving, evidence-based decision making, and prevention-focused thinking.