What if you could identify which 20% of problems are causing 80% of your quality issues, and fix them first? In quality management and process improvement, this isn’t wishful thinking; it’s the power of Pareto analysis visualized through Pareto charts. Named after the Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto, who observed that 80% of Italy’s wealth was held by 20% of the population, this principle has become one of the most valuable tools in business analysis and continuous improvement methodologies.

In 2025, as organizations face increasing pressure to optimize resources and maximize efficiency, the Pareto chart remains one of the seven basic quality tools recognized by the American Society for Quality. Whether you’re implementing Six Sigma, managing projects, analyzing customer complaints, or optimizing manufacturing processes, understanding how to create and interpret Pareto charts is essential for data-driven decision-making.

The art of Pareto charts lies in their simplicity and visual impact. By arranging problems or causes in descending order of frequency or impact, these charts instantly reveal where to focus improvement efforts for maximum return. Research shows that organizations applying Pareto analysis systematically achieve 25-40% faster problem resolution times and significantly better resource allocation in quality improvement initiatives.

In this comprehensive 2026 guide, you’ll discover what Pareto charts are, how they work, when to use them, step-by-step creation procedures, real-world examples across industries, and best practices for leveraging this powerful analytical tool to drive measurable improvements in your organization.

Table of Contents:

- Understanding the Pareto Chart: Definition and Fundamentals

- Components and Anatomy of a Pareto Chart

- When to Use Pareto Charts: Applications and Use Cases

- How to Create a Pareto Chart: Step-by-Step Process

- Real-World Pareto Chart Examples Across Industries

- Pareto Chart Variations and Advanced Applications

- Best Practices for Effective Pareto Analysis

- Pareto Charts in Six Sigma and Quality Methodologies

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

Understanding the Pareto Chart: Definition and Fundamentals

At its core, a Pareto chart is a specialized bar graph that displays categories of data in descending order of frequency or magnitude, combined with a cumulative percentage line. This dual visualization makes it immediately apparent which factors contribute most significantly to an overall effect.

What is a Pareto Chart?

A Pareto chart is a graphical tool that combines vertical bars and a line graph to represent data. The bars, arranged from tallest to shortest (left to right), display individual categories of problems, causes, or factors. The lengths of these bars represent frequency, cost, time, or another measurable unit. Overlaying the bars is a cumulative percentage line that shows the collective contribution of categories as you move from left to right.

This visual representation makes Pareto charts exceptionally powerful for prioritization. At a glance, you can identify the “vital few” factors that deserve immediate attention versus the “trivial many” that contribute less significantly to the problem. According to ASQ, Pareto charts are most valuable when analyzing the frequency of problems or causes in a process, when there are many problems or causes and you want to focus on the most significant, when analyzing broad causes by looking at their specific components, and when communicating data insights to stakeholders.

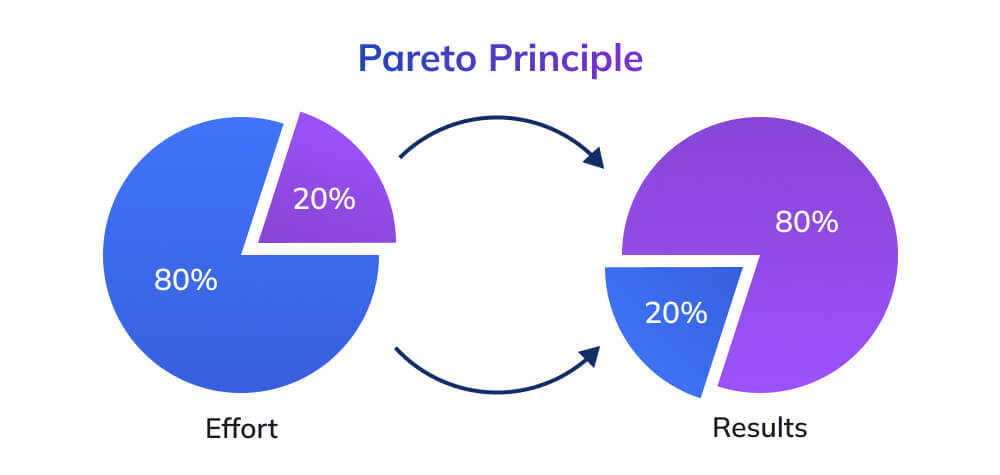

The Pareto Principle: The 80/20 Rule

The foundation of Pareto analysis is the Pareto Principle, commonly known as the 80/20 rule. This principle states that roughly 80% of effects come from 20% of causes. While the exact ratio may vary (e.g., 70/30 or 90/10), the underlying principle remains the same: a small number of factors typically account for most outcomes.

In business and quality management contexts, this manifests in numerous ways: 80% of complaints come from 20% of customers, 80% of sales come from 20% of products, 80% of defects originate from 20% of causes, 80% of delays result from 20% of bottlenecks, and 80% of revenue is generated by 20% of clients. Research from Asana in 2025 confirms that the Pareto Principle remains highly relevant across industries, with most organizations finding that a small subset of factors drives the majority of their results.

Components and Anatomy of a Pareto Chart

Understanding the elements that comprise a Pareto chart is essential for both creating and interpreting these valuable analytical tools effectively.

Essential Elements of a Pareto Chart

Vertical Bars: The primary visual element consists of vertical bars arranged in descending order from left to right. Each bar represents a different category, such as defect types, complaint categories, or failure causes. The height of each bar corresponds to the frequency, cost, time, or other measurement associated with that category.

Left Y-Axis: This axis displays the scale for the bar measurements. It shows absolute values such as number of occurrences, total cost, hours lost, or units affected. The scale must accommodate the largest category value as its maximum.

Right Y-Axis: This secondary axis displays percentages from 0% to 100%, corresponding to cumulative contribution. It enables readers to quickly assess what percentage of the total problem is represented by the top categories.

Cumulative Percentage Line: A line graph overlays the bars, connecting points that represent the cumulative percentage contribution as you move from left to right. This line typically shows a steep initial climb (the vital few) followed by a gradual slope (the trivial many).

Category Labels: The X-axis displays labels for each category represented by the bars. Clear, concise labels are essential for understanding what each bar represents.

Chart Title and Legend: A descriptive title explains what the chart analyzes, while a legend clarifies the measurement units and what the line represents.

How to Read and Interpret a Pareto Chart?

Reading a Pareto chart effectively requires understanding both individual bar heights and cumulative percentages. Start by identifying the tallest bars on the left, these represent your highest-priority items. The cumulative percentage line reveals how much of the total problem the first few categories represent.

Look for the point where the cumulative line reaches approximately 80%. The categories to the left of this point are your “vital few” the 20% of causes creating 80% of effects. These should receive priority attention in improvement efforts. Categories to the right represent the “trivial many”, individually less significant factors that collectively account for only 20% of the problem.

The steepness of the cumulative line’s initial climb indicates how concentrated the problem is. A very steep initial rise means a highly concentrated problem where one or two factors dominate. A more gradual slope suggests the problem is more dispersed across multiple factors.

When to Use Pareto Charts: Applications and Use Cases

Pareto charts excel in situations where data-driven prioritization is essential for effective decision-making and resource allocation.

Ideal Scenarios for Pareto Analysis

Quality Control and Defect Analysis: In manufacturing and production environments, Pareto charts identify which defect types occur most frequently. Instead of trying to address all quality issues simultaneously, teams can focus on eliminating the top 2-3 defect categories that account for the majority of problems. A quality control study demonstrated that focusing on the vital few defects identified through Pareto analysis resulted in 60% faster quality improvement cycles.

Customer Complaint Management: Service organizations use Pareto charts to categorize and prioritize customer complaints. By identifying which complaint types are most frequent or impactful, customer service teams can develop targeted solutions that address the majority of dissatisfaction with focused interventions. For example, if 75% of complaints relate to three specific issues, resolving those three will dramatically improve overall customer satisfaction.

Project Management and Risk Analysis: Project managers leverage Pareto charts to identify which risks pose the greatest threat to project success, which tasks generate the most delays, and which resources experience the most conflicts. This enables strategic allocation of attention and resources to the highest-impact areas.

Sales and Revenue Optimization: Sales organizations analyze which products, customers, or regions generate the most revenue. Understanding that 20% of products might generate 80% of profit enables strategic decisions about product development, marketing investment, and sales force allocation.

Process Improvement Initiatives: Whether implementing Lean, Six Sigma, or other continuous improvement methodologies, Pareto charts help improvement teams identify the process steps, bottlenecks, or error sources that contribute most significantly to overall process inefficiency.

Healthcare Quality Improvement: Healthcare organizations use Pareto analysis to prioritize patient safety issues, reduce readmissions, optimize resource utilization, and improve clinical outcomes by focusing on the most frequent or costly problem areas first.

When Pareto Charts May Not Be Appropriate

While powerful, Pareto charts have limitations. They’re less effective when all categories have roughly equal frequency or impact (no clear vital few), when problems require immediate attention regardless of frequency (safety-critical issues), when the goal is comprehensive improvement across all areas rather than prioritization, or when adequate data for frequency analysis isn’t available.

Understanding these limitations ensures you apply Pareto analysis in contexts where it adds genuine value.

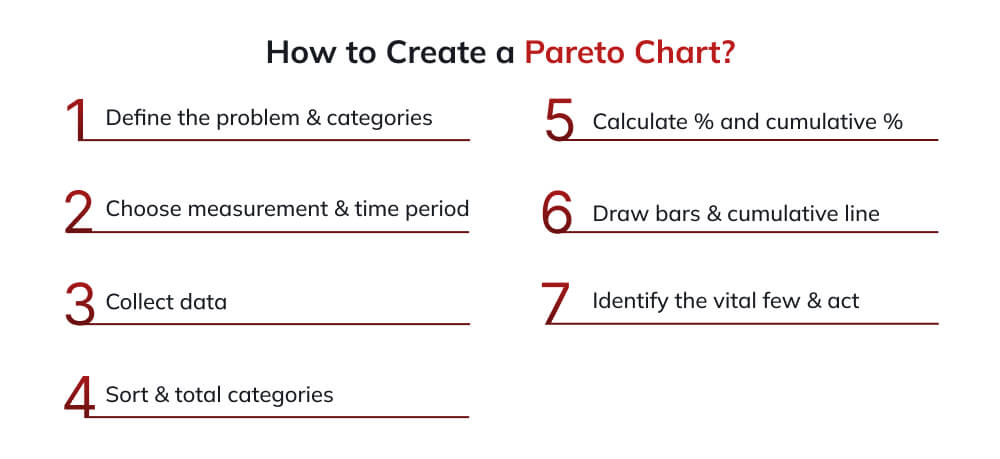

How to Create a Pareto Chart: Step-by-Step Process

Creating an effective Pareto chart requires systematic data collection, proper categorization, and correct visualization techniques. Here’s a comprehensive step-by-step guide.

Step 1: Define the Problem and Data Categories

Begin by clearly defining what you’re analyzing. Are you examining defect types, complaint categories, delay causes, or cost drivers? Establish clear, mutually exclusive categories that will form the bars of your chart. Categories should be specific enough to be actionable but not so granular that you have dozens of tiny categories.

For example, if analyzing manufacturing defects, your categories might be: Surface scratches, Dimensional errors, Color inconsistencies, Component misalignment, Packaging damage, and Material defects. Each category should be clearly defined so anyone collecting data can consistently classify observations.

Step 2: Determine Measurement Method and Time Period

Decide what measurement you’ll use for each category. Common measurements include frequency (count of occurrences), cost (financial impact), time (hours or minutes lost), or quantity (units affected). Ensure your measurement method aligns with your improvement objectives. If cost reduction is the goal, measure financial impact. If throughput is the priority, measure time.

Define the time period for data collection. Will you analyze one day, one week, one month, or one quarter? The period should be long enough to capture representative data but not so long that patterns become obscured or outdated.

Step 3: Collect and Record Data

Systematically collect data according to your defined categories and measurement method. Use check sheets, automated tracking systems, or database queries to gather information. Ensure data collection is consistent and comprehensive throughout the defined period.

For instance, in a customer service context, you might record every complaint received during a 30-day period, categorizing each according to your predefined complaint types and noting relevant details.

Step 4: Calculate Totals and Percentages

Subtotal the measurements for each category. If you collected 500 total complaints, and 150 were about delivery delays, 120 about product quality, 100 about pricing, 80 about customer service, and 50 about website issues, those are your subtotals.

Calculate each category’s percentage of the total: (Category total ÷ total) × 100. In our example, delivery delays represent (150 ÷ 500) × 100 = 30% of total complaints.

Calculate cumulative percentages by adding percentages sequentially. First category = 30%, first + second = 30% + 24% = 54%, and so on until you reach 100%.

Step 5: Sort Categories in Descending Order

Arrange your categories from highest to lowest based on their measurement values. This is the defining characteristic of Pareto charts, the tallest bar always appears on the left, with progressively shorter bars to the right.

Using our complaint example, the sorted order would be: Delivery delays (150, 30%), Product quality (120, 24%), Pricing (100, 20%), Customer service (80, 16%), Website issues (50, 10%).

If you have many small categories, consider grouping them into an “Other” category to keep the chart readable. Typically, if a category represents less than 5% individually, it’s a candidate for grouping.

Step 6: Construct the Chart

Create the Bar Chart: Draw vertical bars for each category in your sorted order. The height of each bar corresponds to its measurement value (frequency, cost, etc.). Bars should be adjacent with no gaps between them.

Add the Cumulative Line: Plot points above each bar representing cumulative percentages. The first point (above the first bar) equals that category’s percentage. The second point equals the first category’s percentage plus the second category’s percentage, and so on. Connect these points with a line from left to right. The final point should reach 100% at the far right.

Label Both Y-Axes: The left Y-axis shows your measurement scale (e.g., number of complaints, 0-150). The right Y-axis shows percentages (0-100%). Ensure the scales align properly so 50% on the right corresponds to the midpoint value on the left.

Add X-Axis Labels: Clearly label each bar with its category name.

Include Title and Legend: Add a descriptive title explaining what the chart analyzes (e.g., “Customer Complaints by Category – October 2025”). Include a legend explaining what the bars and line represent.

Step 7: Analyze and Identify the Vital Few

Examine where the cumulative line crosses the 80% threshold. The categories to the left of this point are your “vital few”, the high-priority items deserving immediate attention. In our example, the first three categories (delivery delays, product quality, and pricing) account for 74% of complaints, making them the clear focus areas.

Real-World Pareto Chart Examples Across Industries

Understanding how different organizations apply Pareto charts helps illuminate their versatility and practical value.

Example 1: Manufacturing Defect Analysis

A mid-size electronics manufacturer tracked 1,250 defects over one month across six categories:

- Soldering defects: 450 occurrences (36%)

- Component placement errors: 320 occurrences (25.6%)

- Testing failures: 225 occurrences (18%)

- Labeling mistakes: 150 occurrences (12%)

- Packaging damage: 75 occurrences (6%)

- Documentation errors: 30 occurrences (2.4%)

The Pareto chart revealed that soldering defects and component placement errors together accounted for 61.6% of all quality issues. The cumulative line showed that the top three categories represented nearly 80% of defects.

Action Taken: The quality team focused improvement efforts exclusively on soldering processes and component placement automation. Within three months, overall defect rates dropped by 58%, demonstrating the power of targeted intervention based on Pareto analysis.

Example 2: Healthcare Patient Readmissions

A regional hospital analyzed causes of 30-day patient readmissions across 500 cases:

- Medication complications: 175 cases (35%)

- Inadequate discharge instructions: 140 cases (28%)

- Premature discharge: 90 cases (18%)

- Infection: 50 cases (10%)

- Patient non-compliance: 30 cases (6%)

- Other causes: 15 cases (3%)

The Pareto chart showed that medication complications and inadequate discharge instructions together caused 63% of readmissions.

Action Taken: The hospital implemented enhanced medication reconciliation protocols and redesigned discharge education processes. Readmission rates declined by 42% over six months, saving an estimated $2.3 million in costs.

Example 3: IT Help Desk Ticket Analysis

An enterprise IT department analyzed 2,800 help desk tickets quarterly:

- Password resets: 980 tickets (35%)

- Software installation issues: 700 tickets (25%)

- Network connectivity problems: 560 tickets (20%)

- Email issues: 280 tickets (10%)

- Hardware problems: 196 tickets (7%)

- Other: 84 tickets (3%)

The cumulative line demonstrated that password resets and software installation issues comprised 60% of all tickets.

Action Taken: IT implemented self-service password reset functionality and automated software deployment tools. Ticket volume decreased by 48%, freeing help desk staff to handle complex issues requiring human expertise.

Pareto Chart Variations and Advanced Applications

Beyond basic Pareto charts, several variations extend the tool’s analytical power for complex situations.

Weighted Pareto Charts

Standard Pareto charts use frequency as the measurement. Weighted Pareto charts incorporate impact or severity, multiplying frequency by a weighting factor to reflect true business impact.

For example, in defect analysis, not all defects have equal consequences. A minor cosmetic defect may occur frequently but is inexpensive to fix and rarely causes customer complaints. A critical functional failure may occur infrequently but can incur significant warranty costs and customer dissatisfaction.

A weighted Pareto chart would multiply each defect type’s frequency by its average cost, creating bars based on total financial impact rather than just the number of occurrences. This ensures resources flow to the highest-impact issues, not just the most frequent ones.

Comparative Pareto Charts

Comparative Pareto charts display two time periods or conditions side-by-side, enabling before-and-after analysis. For instance, you might show defects before and after an improvement initiative to visualize which categories improved and whether new issues emerged.

This variation is particularly powerful for communicating improvement results to stakeholders, demonstrating not just that overall performance improved but specifically where the improvements occurred.

Multi-Level Pareto Analysis

Once you identify your vital few categories, you can drill down into the top category with a second Pareto chart analyzing its sub-components. For example, if “delivery delays” emerges as the top complaint category, a second Pareto chart might break down delivery delays into: carrier issues, warehouse processing delays, incorrect addresses, inventory shortages, and shipping damage.

Best Practices for Effective Pareto Analysis

Maximizing the value of Pareto charts requires following proven best practices that enhance accuracy, usability, and impact.

Ensure Data Quality and Consistency

Pareto analysis is only as good as the underlying data. Establish clear data collection protocols, train all data collectors on category definitions, implement validation checks to catch errors, and regularly audit data quality to ensure consistency. Inconsistent categorization or incomplete data collection will skew results and lead to misguided prioritization decisions.

Use Appropriate Time Periods

Select time periods that capture representative patterns without excessive noise or outdated information. For high-frequency events (like daily transactions), weekly or monthly periods work well. For lower-frequency issues (like major equipment failures), quarterly or annual periods may be necessary to accumulate sufficient data.

Avoid using periods that include unusual events or seasonality that might distort typical patterns. If your business experiences seasonal variation, either analyze each season separately or use full-year data to normalize seasonal effects.

Keep Categories Manageable

Limit your Pareto chart to 5-10 primary categories. Too many categories make the chart cluttered and difficult to interpret. If you have numerous small categories, group them into an “Other” category representing the collective trivial many.

Ensure categories are mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive—every observation should fit into exactly one category, and all possible observations should fit into some category.

Focus on Actionable Categories

Define categories at a level that enables action. Categories that are too broad (e.g., “Quality problems”) don’t provide enough specificity to guide improvement. Categories that are too narrow (e.g., “Scratch on left side of component B-273”) may be too specific for strategic decision-making.

The ideal category level should clearly point to which process, area, or cause needs attention without requiring additional analysis to determine where to focus.

Avoid Common Mistakes

Be vigilant about typical pitfalls that undermine Pareto analysis effectiveness. Don’t assume the 80/20 ratio is exact—the principle is conceptual, and your data might show 70/30, 85/15, or other distributions. Don’t focus exclusively on frequency without considering impact—a rarely occurring but high-cost problem deserves attention. Don’t create Pareto charts without adequate sample size—small data sets produce unreliable patterns. And don’t treat Pareto analysis as one-time—problems evolve, so periodic re-analysis ensures your priorities remain current.

Communicate Results Effectively

The visual power of Pareto charts makes them excellent communication tools. When presenting Pareto analysis to stakeholders, clearly explain the chart components, highlight the vital few categories and their cumulative contribution, connect the analysis to business outcomes and objectives, present action plans for addressing priority categories, and establish metrics to track improvement progress.

Pareto Charts in Six Sigma and Quality Methodologies

Pareto charts play a central role in structured quality improvement frameworks, particularly Six Sigma and Lean methodologies.

Pareto Charts in DMAIC Methodology

In Six Sigma’s DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control) framework, Pareto charts appear prominently in multiple phases:

Define Phase: An initial Pareto analysis identifies which problem areas have the greatest frequency or impact, thereby helping teams select high-value improvement projects.

Measure Phase: Baseline Pareto charts document current-state performance, establishing benchmarks against which improvement will be measured.

Analyze Phase: Detailed Pareto analysis, often at multiple levels, pinpoints root causes and reveals which factors contribute most significantly to the problem.

Improve Phase: Teams focus improvement initiatives on the vital few causes identified through Pareto analysis, maximizing return on improvement effort.

Control Phase: Ongoing Pareto monitoring ensures improvements are sustained and quickly identifies if new problems emerge or old ones resurface.

Integration with Other Quality Tools

Pareto charts complement other quality and problem-solving tools. Often paired with cause-and-effect (fishbone) diagrams, Pareto analysis identifies which categories to investigate, then fishbone diagrams explore root causes within those categories. Check sheets provide structured data collection that directly informs Pareto chart construction. Control charts monitor process stability over time, while Pareto charts reveal which specific issues most affect quality. Scatter diagrams can explore relationships between variables within top Pareto categories.

Conclusion

The Pareto chart is a simple yet powerful way to see which few causes account for most of your defects, delays, complaints, or costs. Used with clean data and basic discipline, it helps you prioritize effort, fix the right problems first, and show clear before–and–after impact to stakeholders.

If you want to use Pareto charts as part of a structured improvement toolkit rather than as a one-off graph, consider Invensis Learning’s Quality Management courses. Our 7 QC Tools training and Lean Six Sigma Yellow Belt program show you how to apply Pareto analysis (alongside other core QM tools) step by step in real projects to drive measurable, repeatable process improvement.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the difference between a Pareto chart and a regular bar chart?

A Pareto chart differs from a regular bar chart in three key ways: bars are always arranged in descending order from highest to lowest value, it includes a cumulative percentage line overlaying the bars showing collective contribution, and it specifically applies the 80/20 principle to identify the vital few factors. Regular bar charts simply display data without this prioritization focus.

2. How do you know if your data follows the Pareto principle?

Examine the cumulative percentage line on your Pareto chart. If the first 20-30% of categories (the leftmost bars) account for 70-80% of the total effect, your data follows the Pareto principle. The exact ratio may vary (70/30, 85/15), but the pattern of a few factors dominating results indicates Pareto distribution.

3. Can Pareto charts be used for positive outcomes, not just problems?

Absolutely. While commonly used for problem analysis, Pareto charts effectively analyze positive outcomes like sales by product, revenue by customer, or productivity by team. The methodology remains identical, identify which 20% of inputs generate 80% of positive results, then replicate or amplify those factors.

4. What should I do if my Pareto chart shows an even distribution with no clear vital few?

An even distribution suggests either your problem is truly dispersed across all categories or you’ve categorized at the wrong level of detail. Try drilling down into major categories to create subcategories, verify your data collection was comprehensive and accurate, or consider whether different measurement criteria (cost vs. frequency) might reveal concentration patterns.

5. How often should Pareto charts be updated?

Update frequency depends on your improvement cycle and problem dynamics. For active improvement projects, update monthly to track progress. For ongoing monitoring, quarterly updates typically suffice. Always update after implementing significant changes to verify their impact and ensure new problems haven’t emerged.

6. What is a weighted Pareto chart, and when should it be used?

Weighted Pareto charts multiply frequency by an impact factor (typically cost, severity, or customer impact) to show true business significance rather than just occurrence count. Use weighted charts when all occurrences don’t have equal consequences, for example, when one defect type occurs rarely but causes expensive warranty claims.

7. Do I need special software to create Pareto charts?

No. While specialized quality software offers advanced features, Microsoft Excel (2016+) includes built-in Pareto chart functionality that handles most needs. Google Sheets can create them with combo charts. Even manual creation with graph paper is possible, though software accelerates the process significantly and enables easier updates.