Continuous improvement isn’t optional anymore; it’s the only way to keep processes stable, costs under control, and customers satisfied. Whether you’re trying to reduce defects on a production line, stabilize a service desk, or fix recurring delays in a project pipeline, the real problem usually isn’t “should we improve?” It’s “what’s the right method to use?”

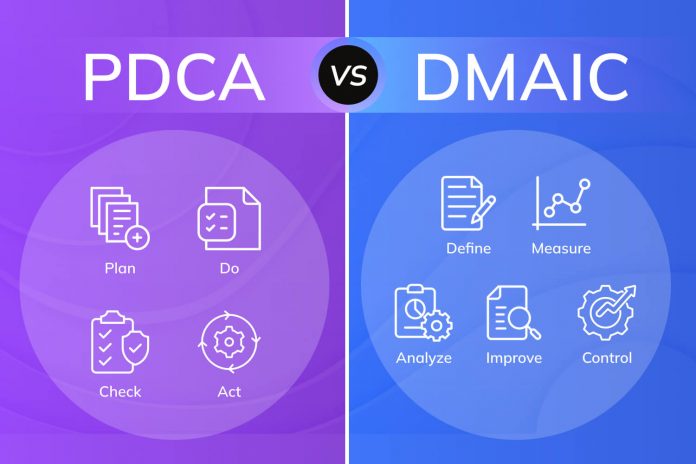

Two of the most widely used approaches are PDCA (Plan–Do–Check–Act) and DMAIC (Define–Measure–Analyze–Improve–Control). Both aim to improve performance, but they are not interchangeable. Pick the wrong one and you either over-engineer a simple fix or under-analyze a complex, high-risk problem. The result: slow projects, cosmetic changes, and “improvements” that quietly fade out after a few months.

By the end, you should be able to look at a problem and confidently decide whether it needs fast PDCA-style experimentation or full DMAIC discipline, rather than guessing or unthinkingly following whatever framework is fashionable in your organization.

Table of Contents

- What Is PDCA (Plan–Do–Check–Act)?

- What Is DMAIC (Define–Measure–Analyze–Improve–Control)?

- PDCA vs DMAIC: The Real Differences That Drive the Choice

- When to Use PDCA?

- When to Use DMAIC

- How PDCA and DMAIC Work Together in a Single Improvement System?

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

What Is PDCA (Plan–Do–Check–Act)?

The Plan–Do–Check–Act cycle is a four-step model for carrying out change, and because it’s cyclical, it’s meant to be repeated continuously rather than used once. It is one of the most widely adopted improvement cycles because it’s easy to teach, flexible across industries, and encourages learning through structured experimentation.

ASQ highlights common situations where PDCA is useful, such as starting an improvement project, developing a new or improved process design, planning data collection to verify and prioritize issues, implementing change, and working toward continuous improvement.

Plan: Define the change and how you’ll know it worked

The “Plan” step is where strong PDCA cycles are won or lost. Planning isn’t just “what should we do?” It includes:

- Clarifying the problem (what is happening vs what should happen)

- Identifying stakeholders and scope

- Predicting what impact a change should create

- Defining success measures (time, errors, cost, satisfaction, throughput)

- Preparing a test plan

The biggest PDCA advantage is that it pushes you to treat improvement as a hypothesis: “If we change X, we expect outcome Y.”

Do: Test the change, preferably small and safe

PDCA encourages testing in a controlled way. ASQ describes the “Do” step as testing the change and carrying out a small-scale study. In practice, this might look like:

- Piloting a revised checklist for one team,

- Running a new form in one region,

- Changing staffing rules for one shift,

- Introducing a new script for one call queue.

The point is speed + learning without risking the entire system.

Check: Review results and learn

In the “Check” phase, you compare outcomes against your plan:

- Did the change improve the metric?

- Did it create side effects?

- What did we learn about assumptions?

- What variation did we see?

ASQ frames this as reviewing the test, analyzing results, and identifying what you learned.

Act: Standardize or adjust, then repeat

“Act” is where improvements become real operations. If the change worked, standardize it. If it didn’t, refine and try again.

ASQ emphasizes that if a change didn’t work, you run the cycle again; if successful, you incorporate learning into broader changes and use it to plan new improvements.

| PRO TIP Treat PDCA as “structured experimentation.” If your team is stuck debating solutions, run a small PDCA test with clear measures, learning beats opinions. |

What Is DMAIC (Define–Measure–Analyze–Improve–Control)?

DMAIC is a structured approach used to improve existing processes that do not meet performance standards or customer expectations. While it’s strongly associated with Six Sigma and Lean Six Sigma, it can also be used as a standalone quality improvement procedure.

ASQ defines the five phases clearly and also provides examples of commonly used tools in each phase. The key idea: DMAIC is not just “do improvements” it is a disciplined path to:

- Define the problem precisely,

- Measure the current state reliably,

- Analyze root causes with evidence,

- Improve with validated solutions,

- Control the process so results last.

Define: Clarify the problem, customers, scope, and goals

ASQ notes that Define lays the foundation: the team defines the problem and goals, identifies customers and requirements, creates a project charter, performs stakeholder analysis, and selects the team.

What “good” Define looks like:

- A measurable problem statement (not just “too many defects”)

- A clear business case (why it matters)

- Scope boundaries (what’s included/excluded)

- A baseline metric plan (how you will track progress)

- Stakeholder alignment (so improvements can be implemented)

Measure: Establish baseline performance with trustworthy data

ASQ’s Measure phase focuses on identifying and documenting the true process, capturing inputs/outputs, validating measurement systems, and establishing baseline performance with trustworthy data.

This is where DMAIC differs sharply from many “improvement meetings.” Instead of jumping to solutions, Measure forces teams to verify:

- do we actually understand the process,

- are we measuring the right things,

- can we trust our data,

- and what is the current capability/performance.

Analyze: Identify root causes and critical inputs

ASQ describes Analyze as identifying critical inputs to determine root causes of variation and poor performance (defects). Tools often used include root cause analysis and failure mode and effects analysis, among others.

The purpose is not just “find a cause,” but validate:

- which causes are real,

- which are most influential,

- and which can be controlled.

Improve: Implement and validate solutions

In Improve, potential solutions are identified and evaluated, the process is optimized, and the critical inputs that must be controlled are determined. ASQ references tools like the design of experiments and kaizen events as examples.

A DMAIC improvement should be:

- linked directly to verified root causes,

- tested/piloted where possible,

- evaluated for cost, risk, and sustainability.

Control: Sustain the gains with standardization and monitoring

ASQ’s Control phase includes mistake-proofing, long-term measurement, reaction plans, SOPs, and establishing process capability. Control plans and statistical process control are among commonly used tools.

This is what prevents improvement from becoming temporary:

- What will we monitor?

- What thresholds trigger action?

- Who owns the control plan?

- How are procedures and training updated?

- How do we prevent old habits returning?

| AVOID THIS MISTAKE Using DMAIC when the cause is already obvious. DMAIC adds value when uncertainty is high and root causes require evidence. If everyone already agrees on the cause and fix, PDCA-style testing and standardization is often faster. |

PDCA vs DMAIC: The Real Differences That Drive the Choice

PDCA and DMAIC are often lumped together as “continuous improvement tools,” but they’re designed for different types of problems and varying levels of rigor. If you treat them as interchangeable, you either:

- Over-complicate simple fixes (running a full DMAIC project when a quick PDCA test would do), or

- Under-engineer complex problems (using lightweight PDCA where you really needed the structure and analysis discipline of DMAIC).

To use them properly, you need to understand how they differ across a few critical dimensions: purpose, speed, data expectations, sustainability, and risk.

1. Purpose and Typical Use

PDCA → Everyday improvement cycle

- Designed for continuous, incremental improvement.

- Great for local problems where you can safely test a change on a small scale (one team, one shift, one clinic, one product line).

- Used heavily in daily management, kaizen activities, and frontline problem-solving.

DMAIC → Structured problem-solving roadmap

- Designed for fixing underperforming processes with clear business impact.

- Best when problems are complex, cross-functional, or high-risk, and you cannot afford “trial-and-error” fixes.

- Used as the backbone of Lean Six Sigma projects and strategic improvement initiatives.

In plain terms:

|

2. Structure: Cycle vs. Phased Project

PDCA = Loop

- Four repeating steps: Plan → Do → Check → Act.

- Once you finish one cycle, you start another, refining or scaling the change.

- Lightweight, minimal paperwork, very easy to teach and embed at the team level.

DMAIC = Phased roadmap

- Five defined phases: Define → Measure → Analyze → Improve → Control.

- Each phase has specific deliverables (charter, baseline, root cause analysis, control plan, etc.).

- Progression is more formal: you shouldn’t move on without completing the previous phase to a defined level.

Practical implication:

|

3. Speed vs. Rigor

PDCA optimizes for speed and learning.

- You can run a full PDCA cycle in days or weeks, sometimes even within a single shift.

- The emphasis is on running a safe experiment, observing what happens, and adjusting quickly.

- Perfect for “We think this might work, let’s test it with real data.”

DMAIC optimizes for depth and proof.

- A serious DMAIC project can run for weeks to months, depending on scope and data needs.

- You spend real time in Measure and Analyze to validate data, understand variation, and prove root causes.

- Perfect for “We cannot be wrong about this, we need strong evidence before we change the system.”

Rule of thumb:

|

4. Data and Measurement Expectations

PDCA = “enough data to learn.”

- Can start with simple before/after measures, small samples, and basic charts.

- Ideal when you don’t yet have perfect data, but can still monitor impact: time, errors, complaints, rework, throughput, etc.

- Measurement can be lighter as long as it’s good enough to detect a meaningful change.

DMAIC = “trustworthy baseline and validated analysis.”

- Requires clear operational definitions, stable data sources, and often measurement system analysis.

- Heavier use of statistics: distributions, variation, correlation, hypothesis tests, capability indices, control charts (depending on complexity).

- Without solid data, DMAIC collapses; you’re basically doing PDCA with extra slides.

If your data is shaky, you either:

|

5. Sustainability: How Each Locks In the Gains

PDCA “Act” = Standardize and continue improving.

- When a PDCA test works, you:

- Update standard work, checklists, or SOPs.

- Train the team.

- Monitor key metrics informally or via simple dashboards.

- Then you run another PDCA cycle to refine or extend the change.

DMAIC “Control” = Formal control system.

- When a DMAIC project works, you:

- Build a Control Plan (who measures what, how often, and what triggers action).

- Implement SPC, mistake-proofing, alerts, and audits where needed.

- Hand over a documented process with clear owners and reaction plans.

Bottom line:

- PDCA provides standardized practice and ongoing cycles.

- DMAIC provides a standardized approach, along with formal controls and governance, especially important for regulated, high-risk, or high-cost processes.

6. Typical Use Cases: Where Each Shines

PDCA is a good fit when:

- You’re tweaking local workflows (e.g., improving a daily huddle, changing form design, adjusting staffing rules).

- The problem is visible and contained (one team, one department, one queue).

- The team can test on a small scale without major risk.

- You want to build a culture of continuous improvement where everyone can run small experiments.

Examples:

- Reducing ticket rework in an IT support queue by piloting a new intake template.

- Shortening meeting duration with a new agenda and timeboxing.

- Improving handoffs between two teams with a simple checklist pilot.

DMAIC is a good fit when:

- The issue has a material business impact (cost, defects, churn, safety, compliance).

- Root causes are unclear, disputed, or multi-factorial.

- The process spans multiple teams, sites, or functions.

- Leadership expects robust analysis and visible, sustained results.

Examples:

- A manufacturing line with chronic defect spikes and no agreement on why.

- A national service process with regional performance variation and customer complaints.

- A healthcare pathway with recurring adverse events and regulatory pressure.

7. Skills, Roles, and Complexity

PDCA:

- Can be led by frontline supervisors, team leaders, or unit managers.

- Tools are simple: basic charts, checklists, 5 Whys, and simple run charts.

- Great for training everyone in the organization to think in improvement loops.

DMAIC:

- Typically led by Green Belts, Black Belts, or trained improvement specialists.

- Involves more advanced tools, such as process mapping, cause–and–effect diagrams, hypothesis testing, regression, FMEA, and control charts.

- Requires more coaching, sponsorship, and project management discipline.

You don’t want to drag a full DMAIC apparatus into tiny, local issues. And you don’t want amateurs winging a PDCA experiment on a problem that could shut down your plant or trigger regulatory action.

| Dimension | PDCA | DMAIC |

| Core idea | Continuous improvement cycle | Structured project roadmap |

| Steps | Plan–Do–Check–Act | Define–Measure–Analyze–Improve–Control |

| Best for | Local, incremental improvements | Complex, high-impact, cross-functional problems |

| Speed | Fast cycles (days–weeks) | Longer projects (weeks–months) |

| Data requirement | “Enough to learn” | Validated baseline, reliable measurement |

| Rigor | Light–moderate | High (especially in Measure/Analyze/Control) |

| Sustainability mechanism | Standard work + repeat cycles | Control plan, SPC, formal monitoring |

| Typical owner | Team leads, supervisors, frontline staff | Green Belts, Black Belts, CI/quality specialists |

| Typical context | Daily management, kaizen, pilot tests | Lean Six Sigma projects, strategic improvement efforts |

When to Use PDCA?

Use PDCA when you want fast learning and incremental improvement, especially when you can test changes without heavy risk.

ASQ lists several “when to use” scenarios, including starting a new improvement project, developing or improving a design, defining repetitive work processes, planning data collection and analysis, implementing change, and working toward continuous improvement.

In practical terms, PDCA is a strong choice when:

- The issue is localized (one team, one workflow, one location).

- The solution is not highly controversial and can be tested quickly.

- You need momentum and engagement from frontline teams.

- You want continuous refinement rather than a one-time breakthrough.

Examples:

- Reducing ticket rework in an IT service queue by revising intake questions.

- Improving meeting effectiveness through timeboxing + new agenda format.

- Reducing handoff errors by piloting a checklist for one department.

- Improving training outcomes by testing a new module sequence.

When to Use DMAIC

DMAIC is best when you need reliable root cause identification and long-term controls, especially for complex or high-risk issues. ASQ notes DMAIC can be used for most projects, particularly if the problem is complex or high risk.

Choose DMAIC when:

- The problem has a significant business impact (cost, defects, compliance, churn, safety).

- The causes are unclear or disputed, and you need evidence.

- You suspect process variation, multiple input factors, or systemic issues.

- Multiple teams/functions are involved (handoffs, governance, shared systems).

- You need a strong sustainment mechanism via control plans and monitoring.

Examples:

- Recurring manufacturing defects where the sources of variation aren’t clear.

- Service-level breaches that vary by region/shift/product type.

- Customer complaints caused by multiple potential failure points.

- High-risk operational errors need mistake-proofing and monitoring.

| PRO TIP In DMAIC, don’t rush Define/Measure. If your baseline data is weak or the scope is vague, your Analyze phase becomes guesswork, and Improve turns into opinion-based change. |

How to Decide Fast: A Practical PDCA vs DMAIC Decision Checklist

Use this quick checklist when you’re choosing between PDCA and DMAIC.

Choose PDCA when:

- You can test changes safely on a small scale

- The problem is relatively contained (one process area/team)

- You need quick feedback and iteration

- The improvement is incremental and not highly data-intensive

Choose DMAIC when:

- The process is underperforming and expectations aren’t met

- The issue is complex/high-risk

- Root causes are unknown and must be proven

- You need long-term measurement and control plans

How PDCA and DMAIC Work Together in a Single Improvement System?

You don’t have to pick a “winner” between PDCA and DMAIC. In a mature organization, they sit at different layers of the same system:

- PDCA = daily/weekly improvement engine

- DMAIC = structured project engine for bigger, riskier problems

Used together, they look like this in practice.

1. PDCA for Frontline, Day-to-Day Improvement

At the team level, you run small PDCA cycles to:

- Fix visible pain points (“this form is confusing,” “this handoff is messy”).

- Test ideas quickly with minimal risk (one team, one shift, one region).

- Build a culture where people expect to experiment and learn.

Result: lots of small, fast wins and better engagement, but some issues will prove deeper than they first appeared.

2. Escalate to DMAIC When PDCA Hits a Wall

Patterns that emerge from repeated PDCA cycles tell you when you’ve outgrown “quick experiments” and need DMAIC:

- The same problem keeps coming back despite multiple PDCA cycles.

- Data from PDCA reveals big variation you can’t explain.

- The issue cuts across multiple teams, sites, or systems.

- The impact is now clearly financial, compliance, or safety-critical.

At that point, you don’t keep spinning PDCA forever, you promote the problem into a DMAIC project with:

- A clear charter (Define)

- Verified baseline and measurement (Measure)

- Evidence-based root causes (Analyze)

- High-confidence fixes (Improve)

- A formal control plan (Control)

3. Use PDCA Inside DMAIC to Test and Refine Changes

Even inside a DMAIC project, you still use PDCA:

- In Improve, you treat each potential solution as a PDCA test:

- Plan the pilot, Do it small, Check/Study the results, Act to scale or adjust.

- In Control, you use PDCA to fine-tune control plans and standard work over time.

So DMAIC gives you the overall structure and governance, and PDCA gives you the tactical testing loop for specific changes.

4. After DMAIC: Return to PDCA for Ongoing Refinement

Once a DMAIC project has:

- Delivered a stable new baseline, and

- Put controls and standard work in place,

you hand the process back to the local owner with the expectation that:

- PDCA cycles continue at the team level to:

- Remove new friction that appears as conditions change.

- Adjust procedures, checklists, and training.

- Keep performance from drifting.

So the flow over time looks like:

Local issue → PDCA experiments → persistent/big pattern → DMAIC project → stabilized process → ongoing PDCA.

That’s how you avoid two failure modes:

- “Big project theater” (everything is DMAIC, nothing moves fast), and

- “Random acts of improvement” (only PDCA, no rigor for big, systemic problems).

Used together, PDCA builds continuous learning, and DMAIC provides heavyweight problem-solving when the stakes are high.

Conclusion

PDCA and DMAIC aren’t competing philosophies; they’re complementary tools in the same improvement toolbox. PDCA gives you lightweight, fast learning cycles that teams can run continuously as part of daily management, ideal for local issues, experimentation, and building a culture of continuous improvement. DMAIC brings greater analytical rigor, validated measurements, and robust control mechanisms for high-impact, high-risk, or cross-functional problems where you cannot afford guesswork. Used together, PDCA becomes your “everyday kaizen engine.” In contrast, DMAIC becomes your “big gun” for complex systemic issues, so you get both speed and depth, quick wins and durable results, rather than over-engineering small problems or under-engineering serious ones.

If you want to move from understanding the concepts to actually leading real improvement projects, this is exactly where Invensis Learning’s quality and process excellence programs come in. Our Lean Six Sigma Green Belt program and Lean Six Sigma Black Belt certification training go deep into DMAIC, root cause analysis, control plans, and data-driven decision-making, while also showing how to use PDCA/PDSA cycles for rapid experimentation and continuous improvement at the frontline.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the main difference between PDCA and DMAIC?

PDCA is a repeatable four-step cycle used to test and refine changes continuously, while DMAIC is a five-phase structured roadmap used to improve underperforming existing processes with validated measurement, root cause analysis, and controls for sustainment.

2. Is PDCA part of Six Sigma?

PDCA is not exclusive to Six Sigma. It’s a general continuous improvement cycle used across many disciplines. DMAIC is more closely associated with Six Sigma as a structured problem-solving approach focused on data and variation.

3. When is DMAIC “too much”?

DMAIC may be excessive when the root cause is already clear, the risk is low, and a small pilot can validate the fix quickly. In such cases, PDCA-style testing and standardization is often a faster approach.

4. Can DMAIC be used without advanced statistics?

Yes. DMAIC can be applied with basic tools, but it still requires trustworthy baseline data and evidence-based root cause validation. The depth of statistical analysis depends on the complexity and risk of the problem.

5. Which method is better for everyday team improvements?

PDCA is usually better for daily management and incremental improvements because it’s lightweight, fast to run, and encourages continuous experimentation and learning.

6. What should I do if PDCA improvements don’t sustain?

If improvements keep slipping back, treat it as a signal to strengthen standardization and monitoring or escalate to DMAIC so you can validate root causes, implement robust solutions, and build control plans to sustain results.